Examining the American Revolution hero, who evaded the British on Lake Champlain, but later betrayed the cause

In the midst of all the memorization associated with history classes back in high school, learning about Benedict Arnold seemed easy. He was the first major American traitor. Granted, I didn’t know exactly how he betrayed the country, nor did I understand why. (I’m still not fully certain about the “why.”)

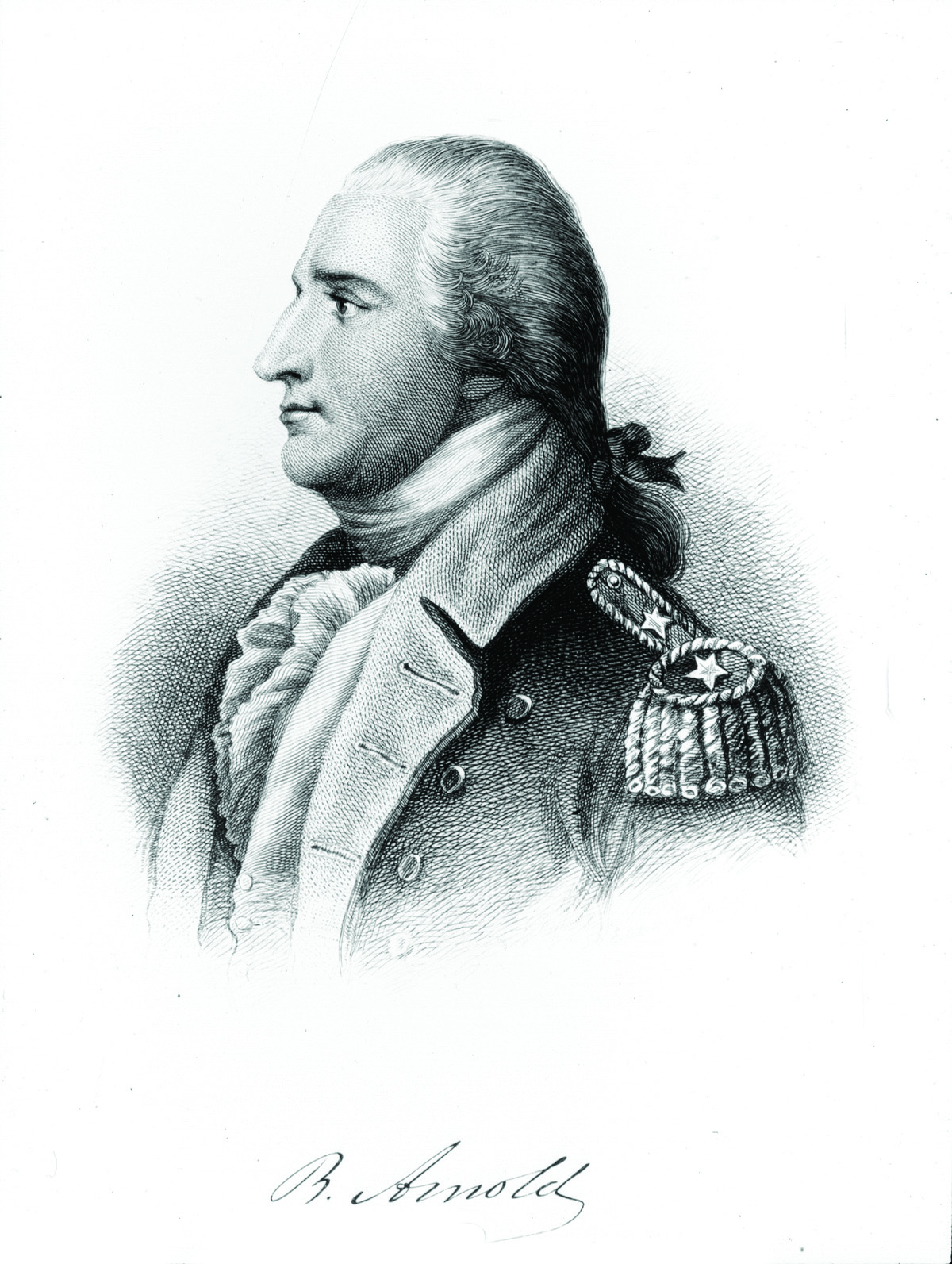

Now, many years later, when I find history to be a magical collection of stories rather than a memory exercise, I learn Arnold may have been the most skilled American officer during the American Revolution. I’ve learned how he betrayed the young union, via his treachery around West Point. The “why” aspect of the equation remains murky.

A recent biography by Jack Kelly, “God Save Benedict Arnold: The True Story of America’s Most Hated Man,” retells the Arnold story in concise, often thrilling fashion. I doubt it’ll be the last word on the controversial hero/betrayer. There may never be a last word on Arnold. But Kelly gives us an illuminating volume.

As rebellion began to fester in the American colonies. Arnold had already had some modest militia training in his hometown of New Haven, Connecticut. Almost from the moment of hearing about shots fired in Lexington and Concord, Arnold showed a readiness for war.

Within months he was alongside Ethan Allen during the takeover of Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. The two weren’t friends, though. Arnold sought recognition as a person of the upper class; Allen represented a tier of society he wished to leave.

Arnold had another attribute that separated him from the Green Mountain Boy. He didn’t think merely about the fighting right in front of him. Rather Arnold had a proclivity for theorizing what might happen next. And next. He became a strategist, a man ready to play chess rather than just another round of checkers. Reconnaissance and planning were as important to his thinking as shooting a gun.

Thus, he was a good choice for a daring invasion of Canada. Moving through Maine to the St. Lawrence River and the city of Quebec isn’t the easiest task even today. One can imagine the obstacles of traversing all those miles of river and unbroken forest in 1775. But Arnold and his troops somehow did so, and this despite untoward weather, loss of supplies and mutiny by an officer. Kelly’s narrative of this episode becomes a gripping one, even though the final incursion into Quebec proved a failure.

From that point, Arnold seemed to be everywhere. Need someone to help hold off Barry St. Leger’s troops coming west along the Mohawk River? Call for Benedict. How about sudden fighting near Ridgefield, Connecticut. You’ll need Arnold. The British fleet attacking Newport? Again, seek out Arnold. Advice for George Washington before that general’s crossing of the Delaware River? Guess who!

But all that came after Arnold spent more time on Lake Champlain early in the war. Charged with establishing the first American Navy, he set up shop in Skenesborough, today’s Whitehall, and got to work supervising the carpenters, wheelwrights, iron workers and riggers. First, however, he daringly sailed north almost to the Richelieu River and captured a British vessel. Towed back to Skenesborough, the craft was turned into the Enterprise. Another, previously captured, became the Royal Savage. Both were in the nascent American Navy’s first flotilla.

MORE TO EXPLORE: See all our “America at 250” content

Arnold, as always, did his homework. He learned enough about Lake Champlain to select an area west of Valcour Island as the place to encounter the Royal Navy. Again, Kelly provides a powerful narrative of the strategy employed in neutralizing England’s superior force, and then, seemingly impossibly, escaping overnight. The British, caught entirely unaware, pursued for a while. By now it was late October, and cold weather was imminent. Rather than continue fighting in difficult conditions, the British sailed back up to Canada, where they spent the winter.

That delay may have proved crucial for the American ability to defeat Gen. Burgoyne’s British Army in the next year’s battles at Saratoga. Arnold proved himself valuable yet again during that fight. His determination to lead a more aggressive assault inspired the soldiers and turned the tide in favor of the American forces. He suffered a severe leg wound in the process.

Kelly encapsulated the man’s uniqueness: “Arnold’s ability to face the possibility of extinction without flinching and to navigate danger with cool equanimity were qualities that made him an indispensable leader in battle.”

If Kelly’s story ended on page 229, after Saratoga, Arnold would be revered among the pantheon from the Revolutionary War, along with Washington, Hamilton, Lafayette, and the others we all know. But there was a lot left to his life, and this early aura of heroism eroded.

There’s plenty of opportunity for conjecture. Feelings of disrespect and ingratitude? All those times being passed over for promotion and raises? Personal financial reverses?

A few things about Arnold need to be told. He endured early personal tragedy. His beloved wife died suddenly at age 30. The death of 34-year-old Joseph Warren at Bunker Hill deprived him of an early comrade-in-arms.

When the Continental Congress wasn’t forthcoming with wages for his soldiers, Arnold dipped into his own funds to pay the men. He periodically contracted personally for food and supplies. Though often arrogant, he tended to be a good listener. Fellow officers were routinely allowed input into decision making. He wasn’t afraid of hard work. Per Kelly, “his mix of firm discipline tempered with compassion won the respect and affection of his men.” They welcomed the chance to fight alongside him. Even in the eyes of George Washington, Arnold ranked as a Patriot among patriots.

But Arnold began seething underneath. Not wealthy, his financial burdens took a toll. More importantly, he failed to get the promotions he sought, and that he felt were deserved. When less qualified men were advanced over him in rank, he not only chafed, he came close to exploding. Threats of resignation came frequently.

On occasion, Washington had to intervene. The commander-in-chief understood the frailty of Arnold’s ego. He realized the man caused some of his own problems, though many of his complaints were valid. More critically, this was one of his most effective and most trusted officers. Arnold was critical to the patriot cause.

Until he wasn’t.

After his injuries at Saratoga, Arnold was relegated to non-combat duties in Philadelphia. This was not a man to sit around. Being stationed in Philadelphia with its cultural events and more comfortable living might have appeased some military men, but not this one. Something Philadelphia did offer Arnold, however, was some new romance, with Peggy Shippen, from a Loyalist family.

Arnold’s betrayal manifested itself in 1780, with his plans to give key information to charismatic British officer John Andre. Patient campaigning had earned Arnold an appointment of leadership in the lower Hudson Valley, including command of the fortress at West Point. A secret meeting of the two was arranged, at which Arnold gave Andre crucial written information needed to implement a plot to oust Americans from West Point.

Things went awry and that plot was discovered. Arnold’s escape feels almost like an old-fashioned melodrama with its close calls and near-misses. Andre wasn’t so fortunate. The British officer was captured, quickly tried and hanged for his role in the affair.

A year ago, I learned the actual messages Arnold gave Andre, which the British officer stuffed inside his boot, still exist. They had long been housed within the New York State Archives. As part of its America 250 commemoration, Westchester County put these on display at Kykuit, the Rockefeller estate near Sleepy Hollow, New York. It’s chilling to read the messages in which Arnold gave necessary details on how the British could infiltrate and take control of the fortifications at West Point.

Kelly’s final chapters inevitably address the issue of why Arnold made his fateful choice. There’s plenty of opportunity for conjecture. Feelings of disrespect and ingratitude? All those times being passed over for promotion and raises? Personal financial reverses? Maybe, for this man with a more than ample ego, simply the failure of others to appreciate the skills and successes he brought to the American cause? After all, even Gen. Burgoyne and other British officers expressed admiration of his qualities in battle.

And, of course, the influence of that young and attractive Loyalist-leaning wife.

Aside from a brief stay in Canada, Arnold spent his final years in England. Despite huge sacrifices on his adopted country’s behalf, he never really gained respect from the population there, either. He died in 1801 at age 60.

The real reasons for his betrayal may never be known. Kelly’s biography won’t be the last one written about Arnold. There’s simply too much still ripe for interpretation. Meanwhile, this well-researched, solidly organized book tells Arnold’s story well, reminding us how critical this man was to the American effort before he chose a course that erased his road to fame.